Andrew Bisits

Intrapartum CTG monitoring in breech presentation

North of England Breech Conference, Sheffield

Day 2

Andrew Bisits is the Director of Obstetrics at the Royal Hospital for Women, Sydney, Australia. His hospital sees over 4,000 births per year. Andrew is working on several initiatives to promote normal birth by

establishing primary midwifery care for women and by attending vaginal breech births. He has also created a vaginal breech training course,

Becoming a Breech Expert (BABE).

Today’s presentation examined the evidence for CTG monitoring in breech presentation. To what extent is there evidence? To what extent are doing it because it’s part of our comfort zone and what we’ve always done?

Andrew does not have firm answers, but finds this topic necessary and helpful to discuss. At this conference, people can think clearly and are invested in the issue. At home where he works, people are so busy and so fearful that they just

react, they don’t

think. Here at this conference, we’re sitting back and thinking, discussing, and trying to look at evidence in the broader context. There are so many pressures back at the workplace that you can’t think about these things.

He will ask two main questions about CTG monitoring:

- Do normal women with normal babies need it?

- Can CTG help make VBB as safe as cephalic vaginal birth?

There are small—perhaps significant—differences between cephalic and breech vaginal birth.

The question of CTG monitoring has to be viewed within the context of the various pressures on providers to intervene: We have this normal process, yet we continually feel pressure to intervene. Some of the pressure might come from evidence, but social pressures and a huge medico-legal industry exert the most pressure. Despite being in an evidence-based era, the pressure to intervene based on factors other than evidence—medico-legal cases, social pressures, various opinions—is huge and cannot be ignored.

Learning from adverse events:

What prompted Andrew to talk about this? He was party to a number of adverse events in New South Wales related to breech. By adverse events, he means neonatal mortality (NNM), perinatal mortality (PNM), or very severe asphyxia. He’s familiar with 8 serious adverse events over the past 2 years: 3 births had mechanical difficulties. 2 births had clearly abnormal CTGs (blindingly obvious ones, no dispute). But the 3 other births had CTG patterns where the outcome was unexpected. Again,

glaringly unexpected.

How breech relates to shoulder dystocia:

25 years ago, the whole approach to shoulder dystocia was terribly primitive. Well-meaning providers would yank, shout, and scream. The baby might have a bad outcome and the staff would be traumatized. If you read textbooks from that time, one instruction was to apply firm traction on the head. That’s been reversed because even though the evidence is not watertight, we’ve systematized the whole approach to shoulder dystocia, and it’s made a difference. He no longer hears about people shouting and screaming. Rather, today it’s very quick and focused:

We got the woman into McRoberts, we did this, we did that, we did the next thing, and the baby came out. The providers followed a series of steps clearly.

A similar thing is possible with breech for mechanical problems; we can make those births safer. Knowing the normal and the abnormal in detail allows us to prevent the majority of nasty mechanical problems in a breech birth. We have to keep thinking about it in a creative way, but it’s manageable.

The tricky question, however, is the issue of intrapartum monitoring and how the baby behaves as a breech vis-à-vis oxygenation. When a CTG is glaringly abnormal, there’s no argument. You do something. You act right away in cases of persistent bradycardia or persistent tachycardia. But most cases are in between these two extremes.

Making breech birth safer

There are 2 achievable goals in making breech birth safer: getting better at resolving mechanical difficulties and acting promptly in the case of clear CTG abnormalities. But that leaves us with the remaining breech births with bad outcomes in which the CTG monitoring does

not indicate a problem.

The evidence for CTG

The next part of Andrew's presentation delved deeply into the literature on CTG monitoring. The evidence we rely on for fetal monitoring primarily comes from cephalic births. He referred to the

2017 Cochrane review, with regard to neonatal seizures. If you looking at high-risk subgroups, the effect of CTG on NN seizures is not as strong as with low-risk groups. That has an implication for breech birth. The nastiest outcomes we have are HIE, including perinatal death. If the effects more obvious in the low-risk group, that

might argue for doing monitoring for breech births, even for low-risk breech births.

Whatever evidence we do have, it’s indirect. The critical point is that CTG monitoring halved NN seizures with no effect on mortality, no effect on longer-term cerebral palsy, but with an increase in cesarean/forceps deliveries. Andrew noted, though, that this short-term difference in NN seizures didn’t translate into longer term CP.

(Rixa's note: Andrew referred to an Irish study but I didn't catch the citation; perhaps it was the 1985 Dublin RCT of IP fetal heartrate monitoring?)

INFANT study

Next, Bisits discussed a recent study by Brocklehurst et al,

the INFANT study (Lancet March 2017). It was a RCT of 46,000 women in the UK. All women had indications for FHR monitoring (traditional risk factors). They were randomized into two groups: CTG with or without computerized decision support. Preliminary evidence suggested that computerized decision support might lead to better outcomes by eliminating interobserver variation and thus more accurately indicate when intervention was needed. This was a very well-designed RCT. The trial groups had very similar demographics and a similar frequency of induction, epidural, cesarean, forceps, and spontaneous birth.

3 years ago, Brocklehurst said that if this study doesn’t show a difference in outcomes, it would really raise questions about the overall value and future of CTG itself.

Andrew noted that big money was fueling this study. He didn’t say this maliciously—but 7% of the NHS budget goes towards settling claims in cases that involve CTG.

7% of the NHS budget! No wonder there’s an incentive to get the best out of CTG and find ways to minimize these huge payout cases.

The study itself found

no difference in outcomes between the two methods of CTG interpretation--this despite big hopes for this new computerized technology. The researchers followed the babies for 2 years after birth: still no differences. Andrew noted that some of the authors dropped out of the study because of the findings.

We’re in an ongoing quagmire regarding CTG in general. And it’s a very messy quagmire. Andrew noted that CTG monitoring is “welded into the fabric of maternity care” because of medico-legal pressures, rather than because it’s effective. Yes, it does have a marginal effect, but it’s not as much as it’s made out to be.

When he talks to solicitors about CTG, they tell him, “What we believe is the CTG. What we hear from the doctors, that’s all subjective. But when we see something on paper, that’s something we can all agree on.” Despite all of its limitations, we are stuck with CTG.

The major conclusion of the INFANT study was that we have to look at other ways of monitoring fetal oxygenation during labor. CTG has significant limitations in being able to reduce major hypoxic damage to babies.

What are the implications of the INFANT study for breech babies? It depends on how you interpret the study! Some people would conclude that you should be doing CTG, others would conclude you don’t need to.

Andrew next referred to a 2016 Finnish study on

CTG in breech versus vertex delivery by Toivonen et al. The authors found that late decels and decreased variability were more common in breech labors compared to vertex labors. For example, late decels were seen in 13.9% of breech vs 2.8% of vertex deliveries, and decreased variability in 26.9% of breech vs 8.3% of vertex deliveries. Overall, the authors found that CTGs are different in breech labors compared to vertex; whether or not those differences are clinically useful is still in question.

Shawn Walker: Yes, I also felt that this study was interesting but not strongly useful for clinical outcomes.

Jane Evans: Why? Do more breech babies have shorter cords so they are pulled more? We need to figure out why. These are all the things that would affect that. Can we measure the stress levels of women who aren’t on CTG vs who are (via a swab)?

Andrew Bisits: Yes, you could do that. There are a number of theories about the cording of breech presentations.

ST-waveform analysis

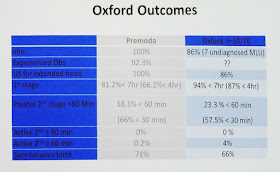

The next study of interest was a 2014 study by Kessler, Moster, and Albrechtsen titled

Waveform analysis in breech presentation (BJOG). The authors took a series of 433 breeches and 5577 vertex babies who were monitored with ST-waveform analysis (a form of fetal ECG, different than traditional electronic monitoring). In theory ST-waveform analysis provides a better assessment of cardiac oxygenation.

Has it proven to be so? Overall there’s no glaring benefit to ST-waveform analysis. There are some enthusiasts, but if you look at the hard evidence, there are no huge standout figures. The vertex group was a higher risk group overall compared to the breech group. See the following slide for details:

There were 3 breech babies with significant problems. See the following slide for details.

In the one case of fetal death, the ST monitoring didn’t suggest an abnormality, nor was it a difficult birth. Maybe there was something wrong with baby? In this case, the CTG provided a falsely reassuring result.

There were also 2 cases of moderate HIE. One was quite severe with nasty seizures. But it wasn’t picked up in the monitoring, nor was it a difficult birth. In the other case of HIE, there was some suspicion due to the CTG tracings.

Overall, 2 of the 3 bad outcomes were not picked up by fetal monitoring. This means CTG/ST has a falsely reassuring rate of 2/500. This compares with the rate of severe outcomes with cephalic high-risk births (2/500). Would this have been higher in the breech group without monitoring? This is the question that is tough to answer.

Main conclusions (from a dearth of evidence):

There are no clear answers about CTG monitoring for breech babies. It’s hard not to recommend monitoring; the social, institutional, and medico-legal pressures are too great. It’s too welded into the fabric of our care. Andrew doesn’t like saying that, but he thinks it’s the reality.

We need to be clear with women about the effectiveness of monitoring, and then a decision can be made whether or not it is done. We also need to look for other methods of monitoring the baby’s oxygenation during labor. Perhaps we should consider the use of buttock lactate/ph. In the 80s, these came up with a lower than normal pH for breech babies. RCOG guidelines said it’s not recommended.

~~~~

Q from Julia Bodle: I’m thinking back to what CTG does and doesn’t do—halving the rate of NN seizures. What are the long-term outcomes for the babies who have NN seizures?

Andrew Bisits: There are 2 differing views on this.

1) In the follow-up from Dublin CTG trial, they could not detect an excess of CP.

2) If you read the Cochrane review and the comments that they invite after it, a Swedish researcher quotes a Swedish study that looks at grade-2 HIE and its longer-term implications. From this particular Swedish study, there is a 48% incidence of CP. Further, 18% of babies had some significant cognitive issue (not sure at what age). Only 25% were actually normal at age 15. NN seizures are not benign in the long-term, according to that Swedish study. I always believed in that Dublin data, so I’d need to look up the original study the Swedish researcher citing.

Andrea Galimberti: In the UK we tend to prefer intermittent monitoring when possible because women can move around. What is the difference between high-risk women monitored and the low-risk women who have intermittent?

Andrew Bisits: From a biological point, nothing! From a psychological standpoint, lots.

Q from audience member: What about other outcomes besides CP, such as ADHD, autism, etc. Have you read anything about this?

Andrew Bisits: There is a weak link with ADHD. The slightly concerning one is cognitive impairments noted at age 15-17. They’re the ones that have been reported in Sweden.

Q from audience member: Might it have more to do with NN management and cooling?

Andrew Bisits: We haven’t changed the instance of CP despite all these advances; it’s still 1/1000.

Q from audience member: There’s no good evidence that any monitoring improves the outcomes because nobody’s done the studies. Certain CFM has known harmful effects. We may be doing a lot of harm while trying to reduce these small things.

Andrew Bisits: In the cold light of day, I would agree with you. The problem is we’ve got this whole mindset that is welded—not by a thread—into the whole fabric of maternity care at all levels.

Q from audience member: Don’t we have to make sure we do no harm, first?

Andrew Bisits: We would hope, yes.

Betty-Anne Daviss: As a practitioner, we have to be very careful in Canada and stay very close to the SOGC guidelines not to raise the ire of the OBs in our unit. I think we have to start understanding what the normal breech is with some of our other parameters. I’m concerned that we’re making the decision about what a normal Apgar is for a breech baby, because Apgars are different for breeches. We have to normalize a low pH for breech babies. We have to put those together with the monitoring. We should start to write down things like floppy/not floppy that seem to raise our concern. As researchers, we need to start putting those things together for what the norm is for breech.

Emilano Chavira: There’s such an obvious parallel between pros/cons of CFM and the breech birth itself. For example, the presentation by Lawrence Impey focusing on all the outcomes of NN survival vs death, and acknowledging that it’s just one outcome and there are so many others we can look at. Your presentation looked at NN seizures/death…but what about everything else—maternal procedures, cesarean sections—that comes with monitoring? I’m very sympathetic about both the audience’s questions and with your presentation. Is there any option at all? Can we engage in informed consent for these things? What approach does the mother want to take? Maybe informed consent is a first step towards dislodging this “welding” that we have.

Andrew Bisits: Yes.

Julia Bodle: This INFANT study affirms my belief that the world is a much more corrupt place than I had thought it was. I just saw a press release from the company that makes the

K2 Guardian CTG technology, the one used in the study, claiming that it reduces stillbirth and brain damage! K2 medical systems is sending these press releases out, clearly misrepresenting the evidence from the INFANT study. In fact, the RCOG and BFMFS just sent a joint statement warning people about this press release. I just got the notice yesterday in my email. It’s outrageous! On the upside, you can use this study in court in your defense; the type of monitoring doesn’t make any difference.

(

Rixa's note: I can not find the RCOG/BMFMS statement online, but I did find this news release mentioning it.

K2 Medical systems is making those claims by comparing the outcomes of the INFANT study with the outcomes of the BirthPlace study.)

Andrew Bisits: Do any units do intermittent rather than routine CTG for breech?

Julia Bodle: The current policy is to talk to the women, give them evidence, and then they choose. Our unit has a policy that it’s recommended.

Andrea Galimberti: We are discussing modifying the policy. And of course women can choose.