First Amsterdam Breech Conference, Day 2

Anke Reitter

New Insights from Pelvimetric MRI Studies

Dr. Anke Reitter is a Fetal Maternal Medicine Specialist at Krankenhaus Sachsenhausen, Frankfurt. She specializes in breech, multiple pregnancies, high-risk pregnancies, ultrasound--and is also an IBCLC!

Anke began with an analogy: if you are in love with a soccer team, you follow them enthusiastically. It’s the same with being a breech activist. Her study will seek to put the data into practice and look at the mechanisms and physiology of breech birth.

She began by addressing the data on term breeches from the university hospital where she had worked with Dr. Frank Louwen. (See the recent publication Does breech delivery in an upright position improve outcomes and avoid cesareans? IJOG 2016; manuscript accepted.) Women came from all over Germany to this clinic to have their breech babies. Now she’s in a new clinic, building up a breech service in a hospital that didn’t previously offer vaginal breech. She noted that most women coming to Frank’s unit for breech births were primips (about 70%).

Anke noted that the RCOG's 2006 guidelines suggested lithotomy position for breech, but the new April 2016 guidelines now endorse all-fours (currently in process, to be released soon). This gives us a safety backup by having this information in the RCOG guidelines. We can change things. The new guidelines also have a summary for safe breech births.

Pelvimetry & Primip Breech

Anke next presented her unit’s safeguards and selection criteria, in particular the role of pelvimetry for primips. She feels that doing MRIs for primips gives them an extra safety cushion. The PREMODA study also recommended “normal pelvimetry.” She referenced a study by Van Loon et al (RCT of MRI pelvimetry in breech presentation at term, Lancet Dec 1997). One group’s MRI data were shown to the physicians, and the other group’s data were hidden. Many factors were the same, but the emergency cesarean rate was lower in the group where physicians knew the pelvimetry data.

Anke wants to compare the Frankfurt MRI data to the Van Loon data—does anyone know how to do this? In the Van Loon study, all women were allowed to labor, whereas her unit excluded some women due to their pelvimetry results.

Anke presented preliminary results from another study she's authoring on primips* with breech presentations. They measured the obstetric conjugates of this group of 371 women. They excluded women with an obstetric conjugate of less than 12 cms (19%). Of the remaining primips who planned a vaginal birth, over 53% had successful vaginal breech births. Annke noted that if you use pelvimetry, you have to accept that you’ll deny some women a chance at a VBB who might have been able to do it successfully. I don't have any more information on this study, except that the manuscript has been submitted.

(*If I understood Anke correctly, this means functional primips, i.e., no previous vaginal births. This could include women with previous cesarean sections).

MRI study on maternal position & pelvic diameters

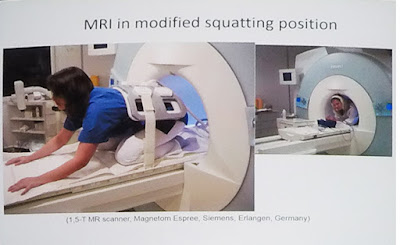

Next, Anke presented results from her MRI study Does pregnancy and/or shifting positions create more room in a woman's pelvis? (J Ob Gyn, Jun 17 2014). The study examined how pregnancy or changing positions changed the pelvic dimensions. They scanned 50 pregnant women and 50 non-pregnant women (mostly midwives from their unit). Each woman was scanned in both a “modified squat" and in a dorsal spine position.

Anke's research team measured the pelvic inlet, the midpelvis, and pelvic outlet (a total of 6 measurements). The results were really exciting: modified squatting makes the pelvic inlet slightly smaller, while the midpelvis and outlet are larger. As midwife Anne Frye says, when the baby isn’t engaged yet, don’t get the woman squatting. Anke commented, "You midwives already knew that, but as a doctor I didn’t know that!"

The same thing happened in the non-pregnant group, and all of the results were statistically significant. Anke was surprised because she’d thought that the obstetric conjugate would widen with a squat, but it narrowed while the other measurements opened.

She also looked at the transverse diameter using several different measurements and noticed striking results: Big changes are happening in the transverse diameters, even more than in the first 6 sets of measurements. They observed the same results in the pregnant and non-pregnant groups. They were very surprised and very happy to see that.

Anke concluded that this MRI study doesn’t mean you have to scan every woman, but it helps explain the advantage of upright positions for both cephalic and breech babies.

Giving credit where it's due, Anke noted that upright birth positions have been used for a long time, especially with midwives.

Anke also mentioned Andrew Bisits’ work in Australia. He recently published his data in Lessons to be learnt in managing the breech presentation at term: an 11-year single-centre retrospective study (AustNZJ Obstet Gynaecol 54.4 Aug 2014.) Although most of the breech births occurred in an upright position on the BirthRite birth stool, his article only spent one sentence describing the mothers' positions. His unit's vaginal breech delivery rate was 58%.

How do we put all this into practice?

Anke noted that we have (re)discovered new maneuvers for freeing nuchal arms and assisting the delivery of the head. With upright breech, we need fewer maneuvers compared to supine breech births (see Louwen et al 2016).

As a side note, Anke highly recommended the MODEL-med obstetric mannequin for simulation training (pictured below). Andrew Bisits has been helping the company improve the doll so the arms articulate correctly.

Know the signs of normal & abnormal with the all-fours position

Normal: the baby's trunk faces forward

Abnormal: the baby's trunk faces sideways

Signs of normal & abnormal rotation with a supine breech:

Anke discussed this 1958 Australian textbook illustration: with a nuchal arm, the body is usually not in a front-facing position—it’s usually transverse. So the arm is drawn correctly, but not the body.

In this 1986 German textbook, she found a good illustration and instructions with the drawings done correctly. You'll see that the body of the baby remains transverse rather than A/P. This illustration shows the proper direction of rotation to try first (the baby's arm points the way).

Direct maneuvers for hands-and-knees:

1. Recognize sign of dystocia (trunk not rotated to the front)

2. To free a nuchal arm: Louwen Maneuver. Rotate 180, then 90 the other direction. Baby's hand points the way for the first rotation. Baby should end facing the mother's anus.

3. To flex the head, do one of the following:

1. Shoulder press or "Frank's nudge": press on the baby's shoulders backwards towards the mother's pubic bone (not downward). Rixa's note: I have seen two variations of the shoulder press, a.k.a. "Frank's nudge," demonstrated at this conference. Anke Reitter prefers holding the baby by its shoulders, the thumb in front and the fingers wrapped around the back of the shoulders. Others place 2 fingers (index & middle) on each shoulder and press backwards gently.

2. Subclavicularly Activated Flexion and Emergence (SAFE): Gently press the sub-clavicular space to elicit a flexion response in the baby. Gail Tully discussed this in depth in her presentation on Day 1.

Indirect maneuvers for hands-and-knees:

1. Gluteal lift: Lifting up the mother's gluteal muscles helps release some soft tissue. This is usually used to assist the birth of the head.

2. Forward lift: Firmly push the mom forward; this pushes her pelvis forward and helps the baby’s head release.

Anke concluded by summarizing the key elements of a vaginal breech service:

~~~~~

Q: In Holland we don’t use pelvimetry. Do you let a multip with a small obstetric conjugate still plan a vaginal breech birth?

A: We do MRI scans on women with no proven pelvis. (I.e., that woman wouldn’t have had an MRI at her clinic since she had a "proven pelvis.")